(Cities were) more than accidental meeting places and crossing points. They were generative environments of the new arts, focal points of intellectual community, indeed of intellectual conflict and tension.

(Malcolm Bradbury and James McFarlane (ed), Modernism: A Guide to European Literature 1890 – 1930)

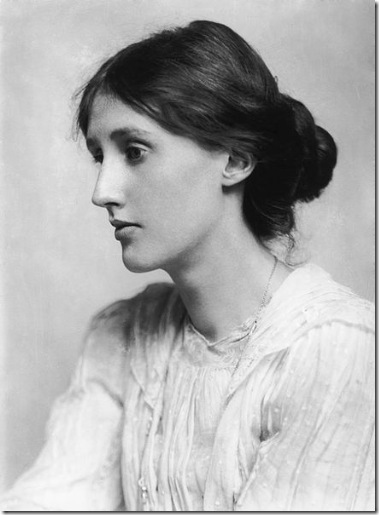

Modernism is very much a phenomenon of the city. Writers from previous generations, Dickens, Gissing and Wells, had all written about London. However, as realist writers, they created narratives driven by plot and character. London was, thus, the backdrop against which these writers’ characters acted out their lives, rather than the city itself being an integral partof the story. Dickens and Gissing’s characters were clearly affected by their experience of urban life. However, early modernist writers, such as Woolf, Eliot, Joyce and Richardson, took this further by exploring, through their writing, the psychological impact that metropolitan life had upon their protagonists; the effect of what Walter Benjamin referred to as the ‘shock’ of life in a modern city.

Modernist writers saw the city as a space to be conceptualised and understood; cities in all their complexity, where spaces overlap and coalesce and are defined variously by economic function, social class, history and topographical character.

Thus, modernist writing had a strong tendency to encapsulate the experience of life within the city, and to make the city-novel or the city-poem one of its main forms. In England, modernism took the form of a reaction by predominantly metropolitan writers against the strictures of Victorianism. London was important to the development of modernism for several key reasons; it was the world’s biggest city in the early part of twentieth-century, having expanded with extraordinary rapidity, and it was the locus of a burgeoning growth of technology and increased mobility. In the nineteenth-century, with writers like Dickens and Baudelaire, artists saw that the city informed the consciousness of its inhabitants. This tradition continued in the twentieth-century with, for example, Joyce’s Ulysses and Döblin’s Berlin Alexanderplatz.

But this was a tradition both embraced and transformed by women modernist writers, most notably Richardson and Woolf. Exploring female personality and the very nature of consciousness itself, they adopted Walter Benjamin’s maxim that ‘life in all its variety and inexhaustible wealth of variations thrives among the grey cobblestones.’ (Walter Benjamin, Charles Baudelaire: A Lyric Poet in the Era of High Capitalism)

In the time in which Woolf was writing, London established itself as the point of concentration for English national culture and established dominance over communication, journalism and the arts. From the 1890s onwards, the average age of marriage increased, women began to enter the universities and the workplace and became more evident on the streets of the commercial centres of major cities. The numbers of such women were not great, but their impact was major and the New Woman was a prominent social and cultural figure of this era. Initially, this new breed of educated, single working woman was represented only in the works of male writers such as HG Wells, with Anna Veronica in 1909 being his most notable example. Whilst there was some support for the New Woman from male writers, many of them had an almost voyeuristic fascination with her sexuality and agonised about her supposed loss of femininity and her reduced prospects of marriage.

However, the early years of the twentieth century saw an explosion in women’s autobiography and fiction that represented an increased sense of empowerment and self-actualisation by women. Alongside this came increased physical mobility for women; not just in terms of opportunities to travel independently outside the family home, but by other changes such as simply being able to wear less constricting clothing. The New Woman became adept at using train timetables and bicycles and a number of, mainly educated Edwardian women, took part in street marches in support of women’s suffrage. By the time of the Great War, women writers, such as Mansfield, Richardson and Woolf, began to write about the types of metropolitan women with whom they were familiar; to write about women from a woman’s perspective:

This simultaneous experience of difference from and yet identification with the walking male writer becomes the central feature of the self-reflexive modernism of Dorothy Richardson, who can be interpreted as progressing from merely borrowing or identifying with the masculinized tropes of attic room and street, to constructing them as the spaces of the woman in the city, the flâneuse.

(Deborah Parsons, Streetwalking the Metropolis: Women, the City and Modernity)

Modernist writers stretched the boundaries of subject matter and form at a pace which reflected that of the fast-moving modern city; they embraced the task of depicting the rapid growth of metropolitan life and the impact that it had on their characters in the fiction that they produced.

Taking up this challenge, Virginia Woolf insisted that her main concern was with the way a story is told, and with the function of the story itself, rather than simply telling a tale. For Woolf, the need to tell a story should not get in the way of the writing. For this reason she abandoned the conventional linear story-telling conventions. Dorothy Richardson came to similar conclusions and explored her resulting ideas in her work Pilgrimage.

As well as a focus on the actual words, Virginia Woolf evolved a new approach to the use of rhythm in her writing too; the pace of life in a modern city was disorientating and intense; gone were the slower rhythms of the countryside, to be replaced by a panoply of sensual inputs. Woolf, and others, suggested that city life affected the rhythms of consciousness itself. This view is reflected in Woolf’s writing and informs her dissatisfaction with conventional realist narrative forms.

She set out to distinguish herself from realist fiction by the use of free indirect discourse, thereby avoiding the falsifying presence of an authorial narrator. In Mrs Dalloway she challenges the very concept of linear time and explores alternatives to traditional storytelling forms. For example, she portrays how the thoughts of people going about their separate business are temporarily bought together by each of them seeing a plane drawing an advert in the sky:

All down the Mall people were standing and looking up into the sky. As they looked the whole world became perfectly silent, and a flight of gulls crossed the sky, first one gull leading, then another, and in this extraordinary silence and peace, in this pallor, in this purity, bells struck eleven times, the sound fading up there among the gulls.

(Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway)

A similar effect is created when a stately car bearing a government crest passes by. Her portrayal of a number of parallel, sometimes overlapping, events is quite cinematic in its effect. Mrs Dalloway is structured around the passing hours of the day, as marked by Big Ben. But the standardisation of time is arbitrary, suggests Woolf. Not just arbitrary, feminist critics have argued, but controlled by men. The masculine Big Ben strikes eleven-thirty and Peter Walsh, worried that he is late for an appointment, is relieved to hear the feminine bell of Saint Margaret’s strike the half hour slightly later:

I am not late. No, it is precisely half-past eleven, she says. Yet, though she is perfectly right, her voice, being the voice of the hostess, is reluctant to inflict its individuality.

(ibid.)

A constant theme of modernist writing is that of generational difference; the conflict between of the Victorian generation and those of the twentieth-century, modern era. It is possible to perceive in Mrs Dallowaya generational difference between Clarissa Dalloway and her daughter, Elizabeth. The approach as to how each one travels the streets of London is very different. Clarissa, born in the Victorian era, walks up Bond Street with pleasure and impunity but does so only, she senses, by virtue of having become ‘invisible; unseen; unknown; there being no more marrying, no more having of children now’ In other words, she is middle-aged, no more of child-bearing age and most likely no longer sexually active.

Elizabeth, born after the turn of the century, rides up Whitehall on a bus, boarding it ‘most competently’ and feeling ‘delighted to be free.’ But if Clarissa’s public consciousness is determined by her sexuality, or by her sexuality as it is construed by others, so too is the daughter’s:

And already, even as she stood there [waiting for the omnibus], in her very well cut clothes, it was beginning…. People were beginning to compare her to poplar trees, early dawn, hyacinths, fawns, running water, and garden lilies; and it made her life a burden to her…. For it was beginning. Her mother could see that the compliments were beginning.

(ibid.)

Since its first use by Baudelaire in the nineteenth-century, the flâneur has proved to be a useful device for writers to employ in their explorations of the modern city. Walter Benjamin conducted a systematic review of the world that Baudelaire had created and set it within a framework of literary, sociological and historical theory. His flâneur was an idle stroller with an inquisitive mind and an aesthetic eye; a solitary figure, he avoided serious political and personal relationships, preferring to enjoy the aesthetics of city life; its material artefacts and human archetypes. The flâneur reads the city and finds beauty in liminal spaces and discarded objects.

The city, though, has traditionally been a male place, with women in a subservient role, or at best at the margins, and this gender bias was reflected in the writing of that period. Benjamin’s work too was notable for the absence of women’s experiences. The writings of Virginia Woolf, and in particular Mrs Dalloway, have done much to redress this imbalance.

Image of Virginia Woolf : Creative Commons

Image of The Mall, 1920s: Courtesy of English Heritage

The post Woolf at the Door 1: The City and Modernism appeared first on Psychogeographic Review.